Solidarity as an Alternative Story of Power

Collective solidarity gives rise to alternative modes and stories of power—in which it is shared, distributed, and kept alive in an interplay of diverse actors.

Solidarity is coming together and saying that we have failed as a society when the survival and existence of a group of people depend solely on charity. It means that we raise our voices to demand that this should not be so. Solidarity shows us the power of compassion and individual agency to help each other, but knowing that ultimately what creates change is people coming together because the crises and experiences of fear, anxiety, depression, loss, and hunger during the pandemic—and beyond it—are widespread public issues that need to be addressed.

It was during those early days of lockdown when Mabi David, one of the founding members of Slow Food Sari-sari, shared this definition of solidarity with me. Following the Covid-19 outbreak in March 2020, it was a time of great reckoning: when we felt hopeless, outraged, disturbed, or all of the above, as we witnessed how disproportionately the pandemic had upended people’s lives.

At the time, a group of us had come together in organizing a food donation and emergency response initiative to, in part, address the immediate hunger that had affected urban poor communities in Metro Manila. Here is one definition of hunger: “the great leveler of humankind, if it wishes to be leveled”¹. These urban poor communities were also the same places that government aid did not reach², places where people feared death from hunger more than the pandemic itself³, where they were militarized, overpoliced, and at times violently dispersed right in our own cities⁴. Some continue not to receive any government aid. Some still have not been heard.

In those early days, we reckoned a lot with the meaning of “solidarity” upon entering the portal of this major crisis. When the nationwide lockdown was first declared (one of many iterations, who could forget), many of us saw how the pandemic exacerbated existing systemic inequalities and injustices, and in fact worsened forms of state and authoritarian abuse⁵. The phenomenon is not unique to the Philippines⁶, but just like fellow democracies under threat, we know it well.

The writer and activist Rebecca Solnit explains this succinctly: In a crisis, “the arrangement of power relations that we call the status quo” begins to unravel, which has long seemed to be stable—till it “changes fast and dramatically, and that can be exhilarating, terrifying, or both.” While “the powerful often try to seize more power” during this time, there is also “an invitation toward a change of consciousness and priorities”⁷: an equally and possibly a more powerful force that motions us toward the collective and the will to act. I believe we witnessed this. We willed new ways of community care, compassion, and solidarity because of it.

The seeds of community and grassroots organizing have been the force of life that, despite it all, keeps us going. In reckoning, there is also refusal: to refuse the notion that what we are experiencing now—in our individual circumstances as well as our public systems—is totally inevitable. In coming together, we can keep making our voices heard. We can empathize deeply. We can show how collective compassion and solidarity give rise to alternative modes and stories of power—in which it is shared, distributed, and kept alive in an interplay of diverse actors. In coming together, we refuse to let the worst continue to happen.

Just as the seed of this book was the initiative we had organized (Lingap Maralita) in the wake of the Luzon lockdown, our group of volunteers, advocates, and activists has since transformed it, adapted it, and continued to reshape a four-month response program into the community of practice as it’s known today: Food Today, Food Tomorrow.

Where “Food Today” provides fresh, organic produce sourced from rural smallholders for community kitchens (kusinang bayan) to prepare meals for households in their care, “Food Tomorrow” grows micro food gardens in the same urban poor communities through training on agroecological farming. What started as a food relief drive in the early days of the pandemic turned into a two-pronged food security initiative founded on the power of community.

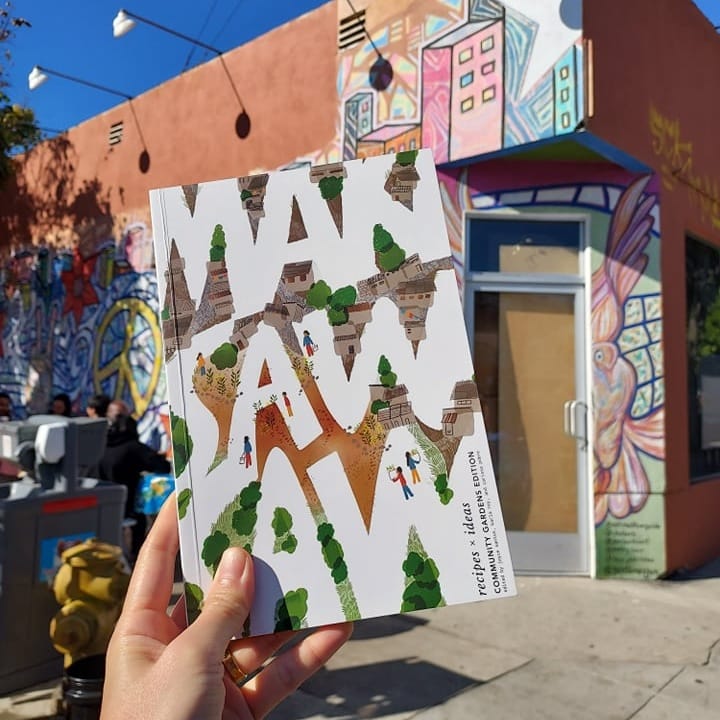

Like the inaugural book that came before it, the Makisawsaw Cookbook: Community Gardens Edition continues the conversation surrounding the food we eat in the context of solidarity: our coming together. Our vision for this cookbook is to advance solidarity with the urban poor and smallholder farmers during these times of precarity and hunger. In it, we connect chefs and cooks, urban poor growers, small farmers, community workers, food justice activists, and healers and restorers of many kinds.

The book in your hands is at once founded on solidarity and community care, and is itself an emergence of it: A plurality of agents. A site of refusal and resistance.

There are many ways to support the Food Today, Food Tomorrow initiative, which remains ongoing. You can purchase a copy of the Makisawsaw cookbook from Gantala Press, online or in local bookstores in the Philippines. You can also purchase solidarity shares from Good Food Community.

Carissa Pobre is a writer from the Philippines and one of the co-editors of Makisawsaw Recipes x Ideas: Community Gardens Editions (Gantala Press, 2021).

References used

¹

From the novel Banana Heart Summer by Merlinda Bobis. 2005. Published by Anvil. Print.

²

Speeches and testaments of Pinagkaisang Lakas ng Mamamayan.

“What went wrong in 2020 COVID-19 ‘ayuda,’ lessons learned for 2021.” April 8, 2021. http://rappler.com/newsbreak/explainers/coronavirus-ayuda-government-aid-what-went-wrong-2020-lessons-learned-2021

³

“‘Walang-wala na’: Poor Filipinos fear death from hunger more than coronavirus.” 2 April 2020. http://rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/poor-filipinos-fear-death-from-hunger-more-than-coronavirus

⁴

“21 protesters demanding food aid arrested in Quezon City.” April 1, 2020. http://cnnphilippines.com/news/2020/4/1/quezon-city-protesters-arrested-.html

“Amid a Pandemic, Evictions Plague the Philippines” by Michael Beltran. October 9, 2020. https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/amid-a-pandemic-evictions-plague-the-philippines

⁵

“How Authoritarians Are Exploiting the COVID-19 Crisis to Grab Power.” April 3, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/03/how-authoritarians-are-exploiting-covid-19-crisis-grab-power

⁶

“Human Rights and Democracy Amidst Militarized COVID-19 Responses in Southeast Asia” by Li-Li Chen. May 13, 2020. https://e-ir.info/2020/05/13/human-rights-and-democracy-amidst-militarized-covid-19-responses-in-southeast-asia/

“The militarization of responses to COVID-19 in Democratic Latin America” by Anaís Medeiros Passos and Igor Acácio. February 2021. https://scienceopen.com/document?vid=898594ae-ca83-4b07-8da4-382650327cbf

⁷

“The impossible has already happened: what coronavirus can teach us about hope” by Rebecca Solnit. Guardian. 7 Apr 2020. https://theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/07/what-coronavirus-can-teach-us-about-hope-rebecca-solnit