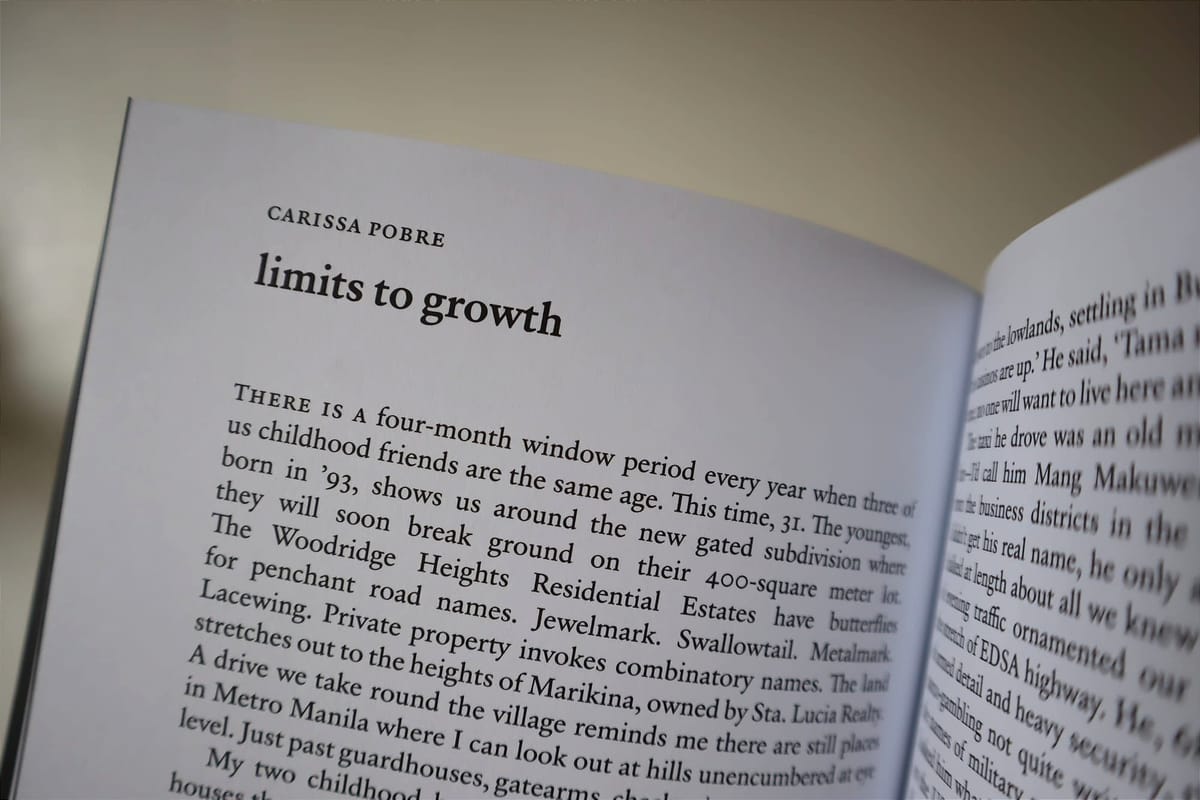

limits to growth

Among the three of us, we always lived in the north part of the city. By that time, no one will want to live here anymore. But I wasn’t sure.

There is a four-month window period every year when three of us childhood friends are the same age. This time, 31. The youngest, born in 93, shows us around a new gated subdivision where they will soon break ground on their 400-square meter lot. The Woodridge Heights Residential Estates have butterflies for penchant road names. Jewelmark. Swallowtail. Metalmark. Lacewing. Private property invokes combinatory names. The land stretches out to the heights of Marikina, owned by Sta. Lucia Realty. The drive we take round the village reminds me there are still places in Metro Manila where I can look out at hills unencumbered at eye level. Just past guardhouses, gatearms, checkpoints.

My two childhood best friends grew up with neighbors with houses that get hired for telenovelas. I eventually took pride in how I didn’t grow up in a gated village in Barangay Bagong Pag-asa, having found it weird as a kid, embarrassing then for me among my early, middle, and high school friends, notwithstanding my father’s addiction to sportscars, making it even weirder. But on the drive we took to the lot of their soon-to-be home, I heard myself asking out loud, ‘Is your place gated?’

That day I went home exhausted and wanting to sleep. All we did the rest of the time was sit and chat at a dinnertable. My two best friends have stable jobs. They save lives, they make joint ventures. I never think anyone is better than anyone else. (They’re always the first to say, I am so proud of you, I love you, I’m so glad whenever I see you in your element.)

At least, among the three of us, we always lived in the north part of the city. Watching time pass through here still got to be different. But, once during a late night commute through the city, I already told a taxi driver—a fellow Ilocano whose lineage went down to the lowlands, settling in Bulacan—‘I will not be here when the casinos are up.’ He said, ‘Tama naman.’ I wanted to add, by that time, no one will want to live here anymore. But I wasn’t sure.

The taxi he drove was an old model Toyota Vios. When I met him—I’d call him Mang Makuwento—I was on my way home from the business districts in the south part of the metropolis. I didn’t get his real name, he only asked for my surname. He and I talked at length about all we knew of what we knew. Brake lights of evening traffic ornamented our cinematic conversation along the stretch of Edsa highway. He, 68, knew more: the dark secrets of armed detail and heavy security, the truths of corpo-politics and narco-gambling not quite written in history textbooks. He knew the names of military projects and weapons, an education to me. I asked him what he transported while working as a contract driver on the US bases in Subic decades ago, and he responded, secret! If you ever meet the nepo Pobre of Tarlac tell him there was a talkative cab driver from the province of Bulacan. Thank you, ma’am. I really enjoyed this conversation. Me too.

The neighborhood girls carry backpacks so heavy it feels like they are carrying the world. Once a scene from my bedroom window, they were a kid walking along my street, a grade school student in uniform. Their backpack was overloaded. Skyblue.

It’s strange, because prior to that cinematic night I met Mang Makuwento, and months before I found out that my best friend ceded to their in-laws’ dream of buying up a lot and building a house for their children, the last time I was in the southern business districts, I was with my mother. My mother and I were walking leisurely around the shopping malls, places I now actively avoid. And it was strange because she herself pointed out and laughed at ‘all the people making porma here’ and then remarked, ‘I contributed to this too?’

That’s when I realized the limits to growth are all in the interactions. I pray they swarm and meld. That’s how desperate I am. I just do not want to live there. Compound and combinatory.

Carissa Pobre is a writer from the Philippines. Her books of poetry and essays include Compositions (2023) and Formations (2021).

Find her books through Everything’s Fine Press at their online shop, or drop by their independent bookstore at 14 Tordesillas Street, Legazpi Village, Makati City.