Notes on Pagkamulat: Routes and Roots of Radicalism

The radical points to a desire close to Marxist and revolutionary thinking, but more rooted and filial as a Filipino through the posing of a question: Paano ka namulat?

In this essay, I make the case that there is a social demand inscribed in the Filipino (Tagalog) notion of pagkamulat, to awaken into one’s political consciousness, that is both a prolonged postcolonial consequence and unique aesthetic preoccupation for those who fall under social locations of the urban educated middle-class. I consider the class composition of this political and cultural question—para mamulat—in the structural context of contemporary Filipino writers, artists, and intellectual-activists who tend to inhabit hybrid positionalities. In doing so, I theorize that social life in the highly urbanized South is conceived primarily through relations of power and precarity, and propose that models of decoloniality in the South have as a political imperative the study of complexities in class formation and power relations, rather than reifying fixed signifiers of identity drawn from a dominant Western episteme.

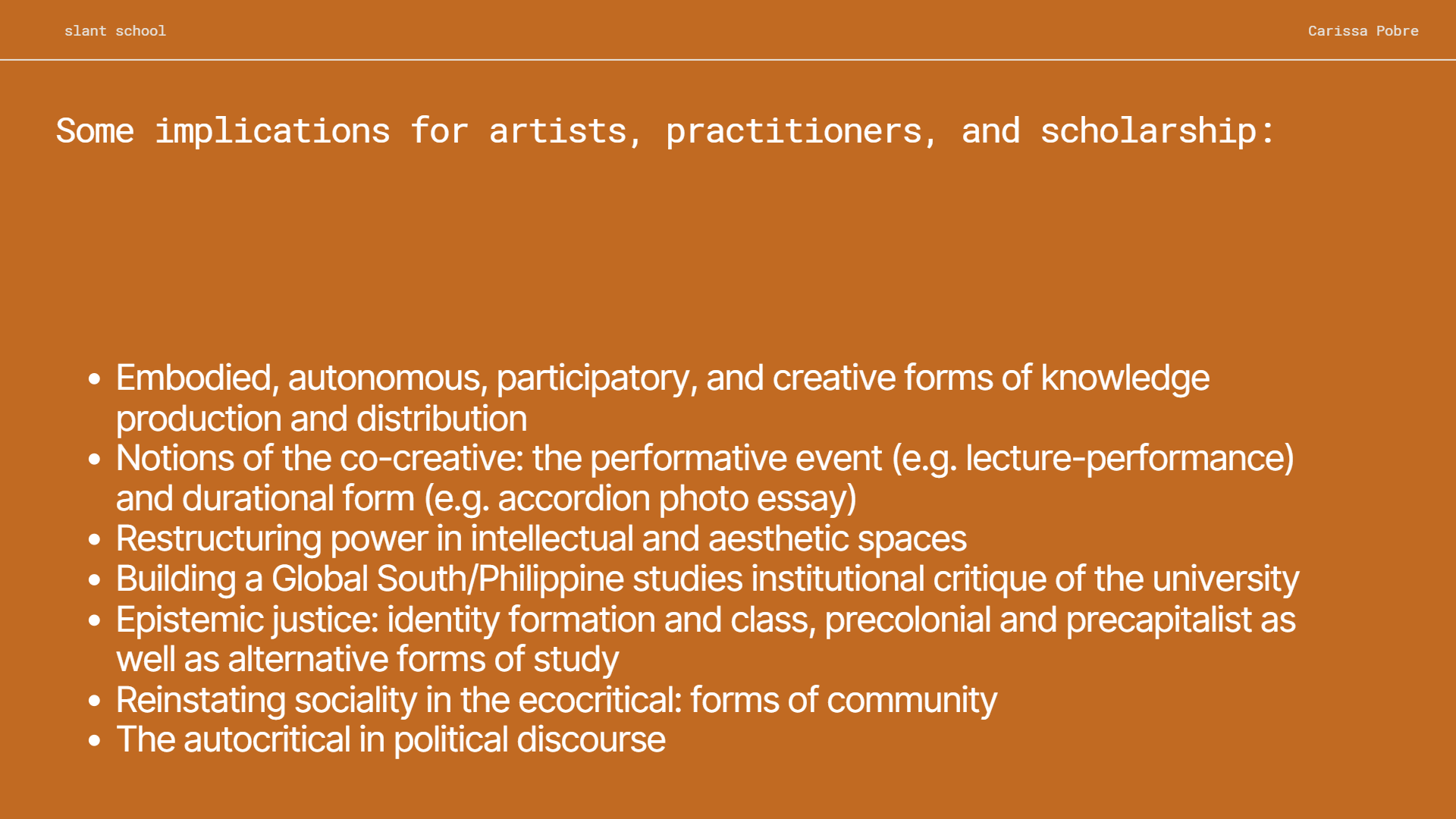

I share this essay as both scholarly context and academic artifact that is interdependent with its embodied methodology, slant school. slant school is an artistic-pedagogic project that enacts this inquiry on politicization and the social formation of the intellectual class. I also suggest by way of this methodology that models of decoloniality must fully embody their institutional and social critique in holding such tensions, particularly in knowledge production and cultural production. Through slant school I at once provide a socio-poetic framing on class politics, institutional education, and place/community, and perform a restructuring of intellectual-aesthetic power relations as a worldmaking project.

Paano ka namulat? A matter of political consciousness

I’ve always had a prolonged, personal desire to understand the political formation of writers. To understand it as a matter of ‘consciousness’—the leap into and latticework of social action. It’s a desire close to what Marxist and revolutionary thinking directs us to, heeding the emergence of the so-called class consciousness, but more rooted and filial to what I’ve experienced and noticed time and again as a Filipino through the posing of a question: Paano ka namulat?

There is hardly a satisfying translation of this word (mulát/múlat from the Tagalog) and this questioning in English; it roughly translates to asking a person how you became ‘conscious’, that is (and the nuance depending on who you’re talking to), how you became politicized or radicalized, enlightened, or aware and educated about social issues, political realities, or truths. It’s a strong shorthand meant to rouse political engagement, opening one’s eyes to what’s happening around us. Oftentimes in the parlance of not only activists, but even politicos and businessmen, you hear a variation of it, na kailangan nang gumising o bumangon ng mga Pilipino (that the Filipino people need to wake up, or can rise up), and you might hear anyone from your parent to your teacher espouse a vibe of the sentiment. Mamulat para sa bayan (for the country), they might say.

One way or another, I think many of us desire for it—ating pagkamulat as Filipinos—and this possibility of bringing about the political consciousness has the heavy, emotional load of confronting how deep your politics goes or how much you’re willing to stake. Or worse, because we simply have no other choice in the matter. Kailangan mamulat (we must awaken, you must open your eyes)—there is no other way.

Posing the question paano ka namulat is also formulated with flair sometimes, presented in the form of a demand: the demand that is (and here I borrow from the Black American poet and scholar Fred Moten) “lodged in times we call political education, radicalization, where we attribute the so-called rupture of one’s political consciousness.” It’s like asking in English, what radicalized you? This signature demand of forming political consciousness (understood to be the class consciousness in the classical Marxist, and perhaps rather Western, sense) is I believe deeply reflective of a prolonged cultural need as a postcolonial country—one that the tides of our history, the chronic constraints of material conditions, the persistence of power grabbing and systemic public ills have repeatedly kept us from ating pagkamulat. From our political awakening. From actualizing a critical mass of our ordinary political power and revolutionary justice, and imagining that all Filipinos could live with dignity here in a just and equal society.

Paano ka namulat? It is, to me, a core contemporary and postcolonial question.

In some sense, I think this is why many Filipinos speak this implicit, or explicit, demand: Mulat ka ba? Mulat ka na ba? (Are you conscious? Are you awake? Are your eyes finally open?) It is, to me, a core contemporary question, an articulation of a social and spiritual question, and a potentially reparative and revolutionary concept, that gets to the heart of a postcolonial project of Philippine society—it’s our very lore, if you will. And it shows up more often in our everyday lives than when one might be talking overtly about politics or activism, or when one might find themselves navigating ideological lines. The yearning lodged inside the cultural notion of pagkamulat is close to that desire which is deeply embedded in common social cues, dispositions, and affects. Mamulat—so that one can show up politically, in some way.

As of this writing, I also want to say, as the national midterm elections have just wrapped up, I believe this concept of pagkamulat/pagiging mulat is deeply entangled with a differentiated though not exactly polar opposite, but simply another fracture of the rough, crystalline subject that is the postcolonial Filipino: the cultural assumption that ordinary citizens are actually likely to hear much more often, “na walang nang pag-asa ang mga Pilipino” (there is no hope for Filipinos), “na wala nang mangyayari o magbabago sa Pilipinas” (nothing will happen or change in the Philippines). Paano nga tayo mamumulat (how will we arise or awaken)—so indeed, what good is the political consciousness, of opening one’s eyes?

Who asks this question? Why do we ask it? How does this social demand toward one’s politicization emerge and manifest: in our private domestic lives, in our public systems, in our respective life choices?

The Filipino writer as an enduring postcolonial problematic

My interest in this notion of political consciousness is seeded in part by my identity as a Filipino writer. It was long refracted as someone who, around ten years ago, took up creative writing during my undergrad when one among the painstaking questions that I, like many others, commonly faced was the relevance of the Filipino writer. This is especially true for the Anglophone one.

The Filipino writer writing in English is a figure whom we can now say is somewhat infamously remarked as being privileged. He (indeed we probably conceive of the Filipino writer as he who writes) is someone who would have been “miseducated”, by aesthetic regimes and cultural institutions largely from the US imperial system through cultural diplomacy and the dominance of American soft power.

I often historicize the years just before 2016 as the height of an anti-establishment wave in contemporary literary history.

Back then, while I was studying, I often historicize this moment in contemporary literary history—the years just before 2016, pre-Dutertism, inside of the liberal milieu of the Obama era and Aquino era alike—as being at the height of some kind of literary anti-establishment wave, precisely critiquing and un-wresting ourselves from these aesthetic regimes. After all, even despite the rich, postcolonial discourse on alterities and hybridities (that we can appreciate for instance in the manifestation of World Englishes, including creolizations and indigenizations of the “vehicular” colonial languages), there is still no greater or more complex representation of elite power and privilege in some ways than Philippine literature written in English. It is, truly, an enduring postcolonial problematic.

To ask, or indeed demand, one’s politicization as inscribed in the notion of pagkamulat points to a postcolonial predicament of birthing a collective political consciousness. It is one that I personally locate as a descendant of the history of the cultural divide between art for art’s sake and literature as agent for social change, and more broadly, that prolonged private and public desire (para mamulat) as a Filipino. The preoccupation with pagiging mulat is broadly evident in our postcolonial social movements, which has long been problematized in the left and produced different cultural responses, all while Philippine literature has straddled significantly with its postcolonial anxieties, in other words, multiple colonialities. To be sure, for contemporary writers who wish to meet the social demand, we absolutely must configure something different.

Ultimately, the class composition/social composition to this predicament and milieu of political consciousness is what interests me most. Just as no one is quite born an activist, nor born a class traitor, how do we rouse and rupture and radicalize: to be aware of one’s place in the broader struggle, and show up for that? As we are lodged in these times of radicalization, what social and institutional forces shape that demand—both historically and in the present?

Class society in the Global South: More than (Western) identity politics

I anchor the sociopolitical force of this inquiry on the epistemic need to clarify how we view social life and class in the highly urbanized Global South. Particularly in Metro Manila, like many other megacities in the ‘developing’ world, we are experiencing the very stark reality where we are living inside of chronic, persistent underdevelopment and overdevelopment at the same time.

Here I use the epistemological construction of the Filipino scholar Neferti X. Tadiar to approach this: where life has been “remaindered” for the majority—for the poor, the working class, the grassroots—many writers, artists, intellectuals in the Global South who are “attuned to the paradoxes of living” have a particular positionality and subjectivity as they “resist from the side of remaindered life”, which she acknowledges as a unique preoccupation. It is, as Tadiar puts it, “a political heuristic challenge” and “an aesthetic problem and intellectual preoccupation” for these classes or class contexts.

Although class is often reified as a marker of identity, it is not always fixed, and this becomes a unique challenge for those of us who resist from the side of the poor, the working class, the grassroots. It is, again, an “[intellectual preoccupation and aesthetic problem] of Global South artists”—for whom this psychic life and social operation of power is stark, and by way of social and cultural capital (especially pertaining to education, employment, and language), are also broadly considered to be middle-class. This matters both materially and affectively.

For us in the Third World, social life is characterized less by fixed signifiers of identity, but rather by relations of power and precarity.

The impoverishment of social life, the intricacies and shared precarities of cosmopolitan existence, as well as the transit from one class or class context to another, underscore the deconstruction of concepts of social life and subjectivity. More so, many of those whom we consider middle-class also share precarities and even poverties with the working classes, and meanwhile the buy-in of the ‘Filipino middle class’ is largely conceived to be the strategic challenge for political solidarity.

It is also knowing, as ‘middle-class’ Filipinos—attuned to the paradoxes of living, with more of the privileges to live a full life—that our lived experiences have always been marked by class-based divisions and extreme inequalities.

As I write in the lecture-performance sociology aslant, for us in the Third World, social life is characterized less by fixed signifiers of identity (as perhaps a dominant, Western identity-based politics would have it) but rather by relations of power and precarity that pulsate in the social demand. Class shapes how we view the world—and because we’ve known our everyday life under the worsening realities of social polarization and cultural segregation, encoded in almost all forms and spaces of contact, more and more of those in a concentrated ‘middle’ only come to appreciate people from different class and social backgrounds largely through exchanges of labor. In this way, social life is based on relations in their constructed role in (class) society that is their manifestation and representation as (stolen) labor.

So is it any wonder, for instance, that midway into Marcos Diktador Tuta Jr.’s administration, the progressive Makabayan bloc organized their senatorial slate this way: magsasaka (farmer) – mangingisda (fisherman) – maralita (urban poor) – dating konduktor (former bus conductor) – tsuper (driver) – nurse – teacher – dalawang representative ng women’s partylist. They are not identifiers in the way that a dominant identity politics would have us check boxes. They are social relations. Perhaps even before the matrix of labor, these are basic functions of how things work in a society.

Perhaps even before the matrix of labor, these social relations are basic functions of how things work in a society.

From a prior moment when decolonization and revolutionary justice met their impasse, we have only really known and tried to understand our everyday social life under what I borrow from Moten as “the neurosis of the demand”: the demand that is lodged in times of political education and radicalization, where we attribute the rupture of one’s political consciousness. Thus, this social demand (paano ka namulat?) is a psychological and spiritual question, which is deeply postcolonial and specific to us in the Global South, in the Third World—from which neocolonialism and more polite idioms took from anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, and class struggle to rearticulate its tensions. It calls to question class composition and the particular subjectivity of the writer, the artist, the intellectual-activist in the Global South. Power, after all, is the “non-full subject”.

Who radicalizes the Filipino middle class?

Understanding there to be a ‘fluid middle’—one that is instructive, potent for radicalizing, and historically and politically important in social mobilization—how does one move through class and social composition in the postcolonial urbanized South?

Social contact across class lines or inter-class contact has always been limited in highly urbanized cities, as many scholars have noted. Most of anyone who lives in Metro Manila also knows that social life here is like class segregation. The irony is that the Filipino middle class, concentrated in mega-urbanized Metro Manila, has emerged to be a “remarkably coherent social identity.” This is perhaps despite the abstract and socially constructed nature of ‘class’ itself: socialized through forms of institutionalized education and upheld by professional consensus—pointing to how ‘middle-class’ points more to this reproduced social order. (As the Filipino sociologist Marco Garrido cites, “Middle-class politics may be considered to be an embodiment of some kind of modern consciousness acquired through higher education and standards of living…”)

Living in times we call political education and radicalization—a rupture born of a postcolonial moment that is still unfolding and we are actively making—the missing piece of the “political heuristic challenge”, as a social demand, is a lived critique of the class in which some of us were born, some of us were raised, and some of us became professionals to maintain.

Those of us who have been in or around the struggle may have learned to call these ‘entanglements’, but institutional and social forces have sublimated in the class war the paradigms of professional consensus. The ‘middle’ in the middle class is fluid—because we all have the capacity to see ourselves in the broader struggle, and we actually expect a lot from the ‘middle class’—but if we ever felt like the middle-class problem, we probably submitted to the professional consensus more than we’d like to admit.

Many of us well know that educational institutions perpetuate social hierarchy and domination. And the sites of neocolonialisms are all professional entities—schools, offices, occupations. Some wax entanglement from within institution, without always building the imaginaries that not only pose alternatives to industry conventions, but also disrupt notions of success, and offer new ones in a much broader web of life. Even as we resist in a socio-civic sphere, the demand itself (drawing from Moten who explicates a poetics of hesitant sociology) is “encased within the constraints of policy, administration, regulation”—legitimate structures to which our social action is directed.

Decolonial scholars know that precarity is a potent political idea. It trains our attention in understanding the hegemony of uneven conditions, and is a vital and necessary tool toward living out one’s critique of capitalism—“leaning away from habit, stepping outside of comfort zones, and changing the modes of critical thinking” so that we can produce the tools necessary for undoing institutional and social forces.

Although ‘precariousness’ may be no stand-in for a kind of a ‘middle-classness’ born of a prevailing social order—in the way that the Global South artist or writer who resists from the side of remaindered life may sometimes be comparatively less precarious than others—I’ve started to think this is why the figure of the student (the student activist, the insurgent turn) is so activated in our class politics, our postcolonial history, our literature.

The social composition of radicalism: Who radicalizes who?

The aesthetic-pedagogic project of slant school is my embodied manifestation of such questions. Using this ‘method’ of inquiry, and entering into such a worldmaking project, I generally highlight the role of the intellectual classes (university-educated), through the specific figures of the writer, the artist, the intellectual-activist, as well as the student and the professional, and the ways they are or become class actors—between class cogs and class traitors—in contemporary Philippine society. And what I imagine that slant school performs is a socio-poetic framing of that class, if not a poetic sociology of that class.

It is, indeed, about positionality: subjectivity and doing the work of heavily politicizing this—when you are straddling multiple colonialities, while also interrogating the very framings of what we consider to be decolonization, and resisting neat and somewhat identitarian explanations. As a writer, broadly a cultural worker, and indeed a citizen of this imagined national community, in a way what I am repeatedly asking through slant school is, whose problem is it being a problem, and what is the class composition of this problem?

slant school is envisioned as a lifelong artistic-pedagogic project: an idea of a writing school, that is open to different ways of organizing a writing school, and experimenting across art and literature, critical pedagogy, and radical self-critique. I consider it in conversation with autonomous forms of study—what academies and institutes industrialize as knowledge production—and artist-run programs and projects where one actively resists the objectification of an intellectual, creative process into a commodity. I also suggest by way of this methodology that models of decoloniality in knowledge production and cultural production must fully embody their institutional and social critique in holding their tensions.

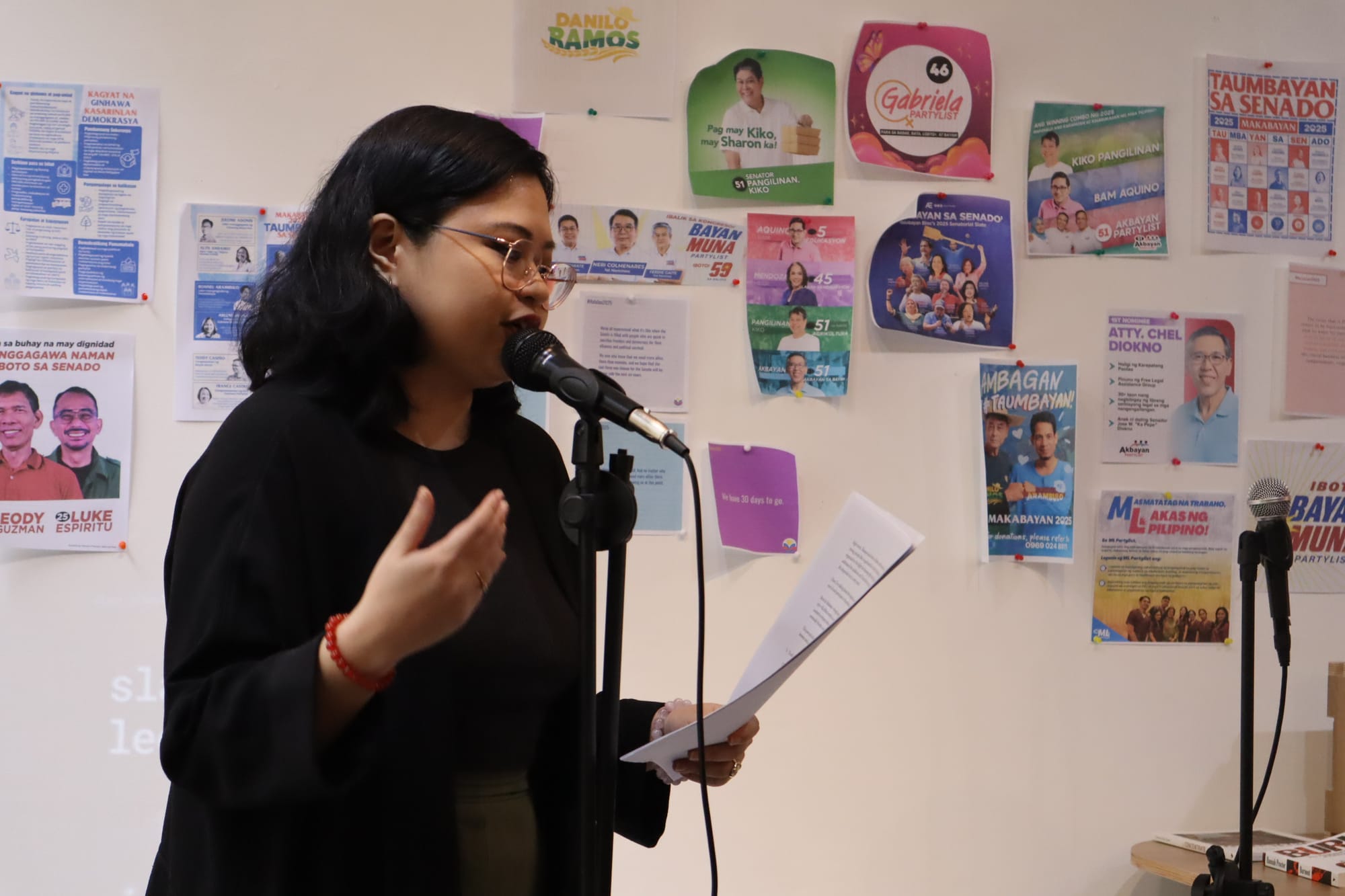

In slant school’s inaugural set of activities—a series of independently organized experimental lectures that were held in Metro Manila and Baguio in April 2025—I wrote, convened, facilitated, and performed three experimental lectures, as a multidisciplinary inquiry into the social formation of the Global South intellectual-activist. Each inquired respectively into class (class politics and the middle class), education (institutional education and the role of the university), and place (especially pertaining to one’s sense of community and mobility). All the lectures were organized with collaborative, co-creative processes, together with various configurations of scholars and students, writers and artists, as well as specific aesthetic and pedagogic modalities.

A. The middle class problem

- sociology aslant

(re)reading and (re)writing social relations under duress of the world order

Reading class relations in Philippine society, and explicating the middle-class problem in the urbanized postcolonial South.

ABSTRACT

As a Filipino, it’s my personal dream to explain the state of class relations exhaustively. I’ll tell you why I have this dream. Which has been more like a fever, more like an illness. Give up on that premise, even scholars will tell you—unless you’re courting a kind of madness, or speaking in high theory, it’s right pointing out that you cannot really give an exhaustive account of something like it. Class, a defining feature of the experience of Philippine society, is both abstract and material, acute and slippery in all the ways that Filipinos (consciously or unconsciously) understand their identity. In fact not only their identity. But their possibility.

Lecture-performance in Makati City

April 12, 2025

B. The idea of the university

- development aslant

disarming the university: a dialogue

Locating the regime of global development to the university, and reinstating the role of students in remaking history and society.

ABSTRACT

The walk through the university gates—any university gates—feels unusually long. One afternoon I walked out of the halls, passed beyond the gates, and the entrance and exit out of the university made me vow only to be in places where people are actually talking. And I began to think the best way to go about undoing the regime of global business is by ‘disarming’ the university: that is, deconstructing and clarifying its current role in global society, its machineries and entrenchments, and its own history of development. Disarming it as a way to court infinitude. Capitalist economic imaginaries are schooled, supplied, and sustained by the university. As with intelligence—needs a lot of breaking.

Online dialogue

April 23, 2025

C. Thisplacemeant: place/community

- ecocriticism aslant

contending with place: postcolonial writers and the politics of the town

Telling stories of place and town, and contending with our plural identities by writing together.

ABSTRACT

This experimental lecture will reflect on the meaning of place and places in our lives, especially as writers and artists. With dialogue and reflection, we will co-create a collaborative photo essay on the places that make us, using our own photographs and written responses to creative prompts. Together we will understand one’s sense of place in terms of community/ies, identity/ies, and political units that tend to organize our place-based notions.

Collaborative photo essay/accordion book installation in Baguio City

Workshop held on April 26, 2025

Thus, slant school seeks to continually understand in particular the postcolonial writer’s subjectivity, and the forces of institution and socialization both that shape an intellectual-activist figure from a Global South context. For one who works toward dismantling power relations, reconfiguring and responding to that social demand through intellectual, literary and artistic work, it must be done through a fully embodied space—in which positionalities are not only statements and new processes shape intellectual resistance. For slant school, it does so through aesthetic co-creative experiments in the realms of knowledge production and cultural production. As a worldmaking project, this ‘school’ is fundamentally about how we write, how we read, and how we study—and how we organize all that.

Evidently, the prolonged postcolonial challenge of pagkamulat is one that is interlocked with class contexts and power relations, borne of multiple colonialities in the crisis of development, as well as the social reproduction of the professional consensus. Pagkamulat/mulát/múlat is also, again, a potentially reparative and revolutionary concept, that can point deeply to the cultural and historical melange of the postcolonial Filipino.

And so too from the demand inscribed within it (to awaken our consciousness), we can further trace possibilities in our decolonial organizing and revolutionary thinking: not only as we actualize and wrestle with ourselves in our sites of culture—our writing, our art, our response—but also, I believe, through such restructuring of power relations and the interplay of forms, gesture toward epistemic justice.

Carissa Pobre is a writer from the Philippines, and a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in Interdisciplinary Art and Regenerative Culture from the University of New Mexico.

Her graduate thesis was advised by Szu-Han Ho (committee chair), Kency Cornejo, PhD, Edward Morris (Sayler/Morris), and Vincenz Serrano, PhD.

Contact me at carissapobre@gmail.com for queries, discussion, or feedback.

Visit http://slant.school for the full project. All shortcomings are mine.

Works cited and consulted

Aguilar, Delia. Toward a Nationalist Feminism. Quezon City: Gantala Press and Kritika Kultura, 2023.

Alvarez, Natalie, Claudette Lauzon, and Keren Zaiontz, eds. Sustainable Tools for Precarious Times: Performance Actions in the Americas. Cham: Springer Nature, 2019.

Barrios, José Luis. Paradox and the Discourse of Inclusion? Lecture at SOMA. Mexico City, July 17, 2024.

Bennett, Eric. “How America Taught the World to Write Small.” Chronicle of Higher Education. September 28, 2020. Accessed October 16, 2022.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage Publications, 1990.

Bunz, Mercedes, Birgit Mara Kaiser, and Kathrin Thiele. Symptoms of the Planetary Condition: A Critical Vocabulary. Luneburg, Germany, 2017.

Cayanan, Mark, Conchitina Cruz, and Adam David. Kritika Kultura Anthology of New Philippine Writing in English. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila U, 2011. Web.

Cruz, Conchitina. Authoring Autonomy: The Politics of Art for Art’s Sake in Filipino Poetry in English. U at Albany. 2016. PhD dissertation. Albany ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

De Sousa Santos, Boaventura. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. London and New York: Routledge, 2014.

Faysal, Yasif Ahmad and Md. Sadequr Rahman. “Edward Said’s Conception of the Intellectual Resistance.” American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 1 (4): 236-243, 2013.

Garcia, J. Neil. “Alterity and the Literature Classroom (Or, I Look for the Other When I Teach).” Humanities Diliman 12:2 (2014): 1-28. Web.

Garrido, Marco. The Patchwork City: Class, Space, and Politics in Metro Manila. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 2019.

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1997.

Graeber, David. “Anthropology and the rise of the professional-managerial class.” Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4 (3): 73-88, 2014.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. New York: International Publishers, 1971.

Guillermo, Ramon. “Post-Cold War Transformations of Global Literary Capitals in the Dissemination and Circulation of Southeast Asian Literatures.” Aguipo Global South Journal 2 (2023): 24-41. Web.

Hau, Caroline. Elites and Ilustrados in Philippine Culture. Ateneo de Manila U P: Quezon City, 2016.

Jaquet, Chantal. Transclasses: A Theory of Social Non-reproduction. London and New York: Verso Books, 2023.

Moten, Fred. Manic Depression: A Poetics of Hesitant Sociology. Northrop Frye Lectures. Public lecture at U of Toronto. April 4, 2017.

Moten, Fred and Stefano Harney. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. New York: Minor Compositions, 2013.

Ortega, Arnisson Andre. Neoliberalizing Spaces in the Philippines: Suburbanization, Transnational Migration, and Dispossession. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila U P, 2016.

Pante, Michael. A Capital City at the Margins: Quezon City and Urbanization in the Twentieth-Century Philippines. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila U P, 2019.

Pobre, Carissa. sociology aslant: (re)reading and (re)writing social relations under duress of the world order. Lecture-performance in Makati City. April 12, 2025.

Pobre, Carissa, Stefano Harney, Ninon Espiritu, and Ramya Espiritu. development aslant: disarming the university. Online dialogue. April 23, 2025.

Pobre, Carissa. ecocriticism aslant: contending with place. Collaborative photo essay/accordion book installation in Baguio City. April 26, 2025.

Santos, Gabbie. “Rising Filipino middle class: Allies for national democracy?” London School of Economics Southeast Asia Blog. November 23, 2021. Accessed January 22, 2024.

Tadiar, Neferti. Remaindered Life. Durham: Duke U P, 2023.