Reading as a Relational Practice

We are readers and listeners of each other, relational, constantly unfolding, re-infolding and taking shape.

On April 24, 2020, at 4:28PM, a friend of mine had asked me to write 30 journaling prompts that, ever since, changed the way I understood my practice as a writer. It was about a month or so into the hard lockdown at that time. The first one, that completely changed our lives with its bold, CAPITAL letters everywhere: ENHANCED, COMMUNITY, QUARANTINE. These days we scroll through BIG WORDS like that and wonder how so many iterations could be wordsmithed around the same thing. Some writers like to say language is play. Just as much, it is ploy.

At that time, early in 2020 the year that was, many people—many of us—were stuck in our homes. Quarantined, domesticated/over-domesticated, isolated/hyper-isolated. Spending all that time at home, indoors. Just as life had changed forever, and we all did our best to avoid any chance of contamination, I helped out my friend with this simple, innocent request: she wanted prompts to write in her journal, like we all were finding things to do, finding ways to reckon with what we were going through, and still do. (Personally I don’t think we yet have the vocabulary to fully describe the wound culture we’ve cultivated because of these times. After all, one might argue that 2020 is still happening now.)

So I wrote my friend the Pandemic Diaries: 30 Prompts—which I believe you all have copies of: its first iteration as a tiny, letter-sized PDF. I wrote that in one, frenzied night. I think I stayed up till about 3 or 4 A.M., then some hours later emailed the prompts to her.

Prior to that, I wasn’t actually considering journaling very much. Mostly, after losing 90% of my full-time job and I could afford not yet looking for a new one, I volunteered my free time to emergency response initiatives, which were happening all over the city, owing to the harsh lockdown restrictions. We were fundraising constantly, and in between the hours and days, I tried it all out. Doodle! Draw! Bake Cookies! Meditate! Try to Stay Grateful! More Webinars!

2020 was also the same year I was “supposed to” enter Columbia University for an MFA in Nonfiction Writing. I say “supposed to” attend Columbia, in sort of the same way that Donald Trump was “supposed to” deport international students when all universities shifted to taking online classes—there was no point of holding space for their bodies anymore in the “Land of the Free”. There was an ICE directive and everything. He was really going to do it, like I was really supposed to find 200,000 US dollars in tuition fees that would not least deplete my mother’s retirement savings and certainly sell my life to the US higher education system, so I could pay to be in debt.

But: Being accepted for the MFA in Writing at Columbia, just before the pandemic changed people’s lives, was certainly a dream come true. I spoke to Leslie Jamison, one of my favorite nonfiction writers, and it’s still as surreal and nourishing to me as when I had just experienced it. Speaking with one of the writers whom I’ve looked up to for so long, all of whose nonfiction books I had finished reading—right before the pandemic in fact. I remember one of the first things Leslie said to me on our call was: “You can never really opt out of your government.”

She said that despite everything, it was talking to admitted students, slated to enter in the fall of 2020, that still gave her a sense of hope, even under such dire circumstances. Speaking to students who liked writing and chose to study writing, I guess that meant there was still a future in sight: an arrival, a ritual, an entryway or portal, still bounded up in time. And even if the fall of 2020 would mostly be online (as it did turn out to be), she seemed to suggest, moving forward was still possible. I myself had returned to my own writing practice—after some of the best years of my early twenties working a good job, until that was that. I got into Columbia. Go to Grad School! Go International! Be a Writer!

To some friends, I emailed them a copy of the 30 journaling prompts I wrote, precisely to help reckon with these strange times, with disappointment and change, with things falling out and falling apart. In order to make sense of things, and to rekindle a sense of agency when we feel that things are just happening to us. How might we begin to rekindle this within ourselves, with language, when one cannot opt out of the story being written? Some of the people I initially emailed the 30 Prompts included:

- A friend doing their masters in the US

- An international student who went through the pandemic completely alone.

- A friend of mine who’s an investment banker who reads a lot of Kafka and The Atlantic, who responded back to my email, saying, “Hmmm… I may actually do this.”

- Another is a journalist.

- Another—over the course of the pandemic—becomes an activist.

- Another was a Creative Writing student a few batches below me whom I knew ambiguously by social media, but like me, she wrote with the 30 prompts every single day, for 30 days.

- One of them I knew from work was a former Lit major who—if travel had not changed—would be diving in our oceans, swimming with sharks or releasing sea-turtles to the shore.

- One of them was a poet I knew.

- One of them is a professor in this room.

For a while, with the prompts, I was writing every day. What happens to your body if you write every day? What would happen to your body? to your senses?

Relationality and Readership

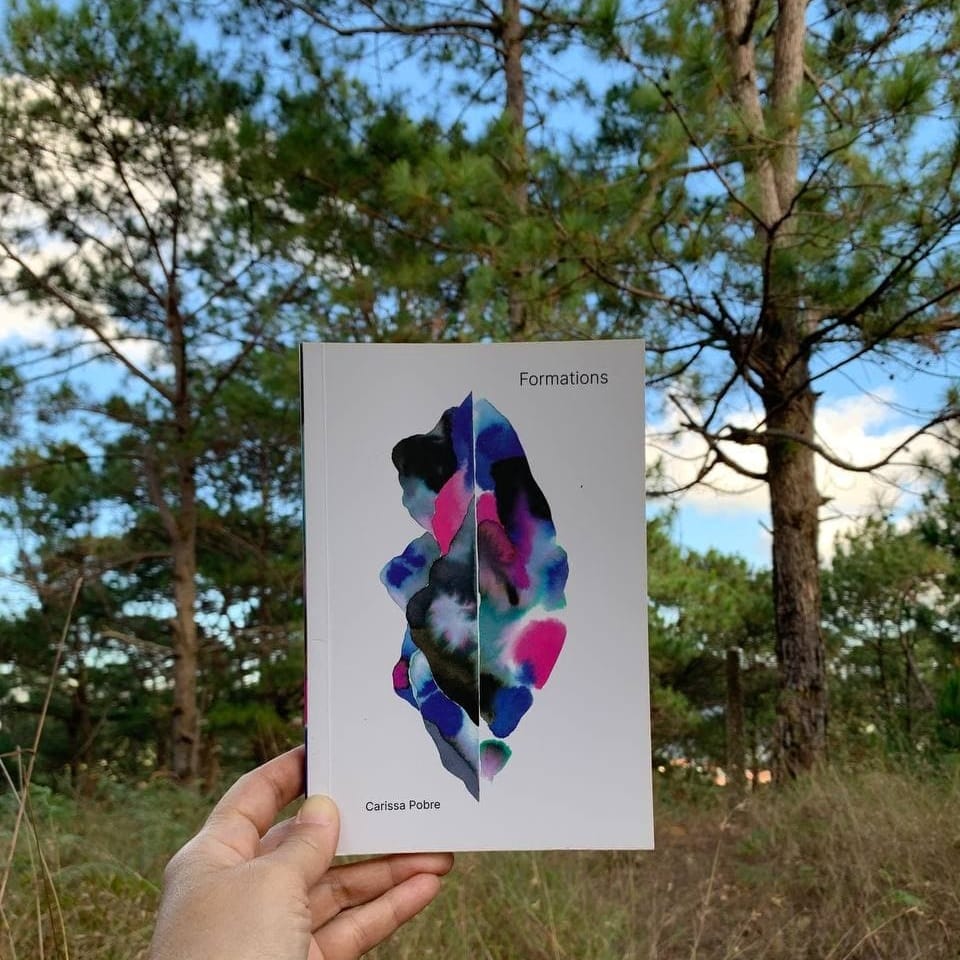

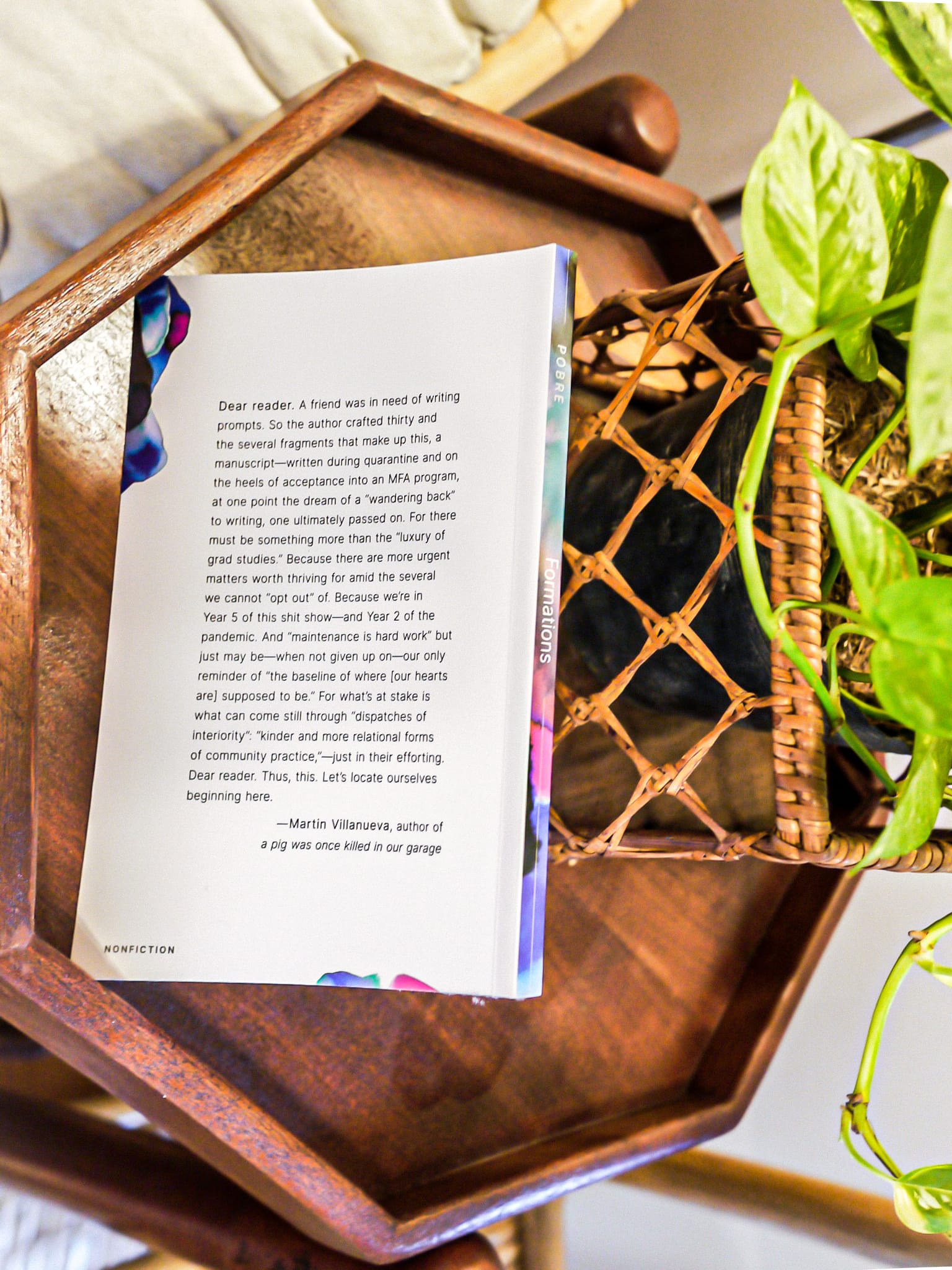

Fast forward to today. I never anticipated that a book of my own, titled Formations, would emerge from my personal writing and journaling process. In hindsight, maybe I should have— at least now I realize that coming out with this book might’ve been a seed planted in my head, by one of my favorite writers— after I had the wild chance to meet her, have a conversation with her— even if I never did go to Columbia— CONTACT IS CRISIS— I am reminded of this line from Anne Carson. She writes: “As members of human society, perhaps the most difficult task we face daily is that of touching one another. … As the anthropologists say, ‘Every touch is a modified blow.’”

After all, it was Leslie Jamison who contacted me as my faculty caller, and it was during that call she had mentioned this other book to me: Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick. Published in 1979 THE YEAR THE SOVIETS INVADED AFGHANISTAN THE SAME YEAR THAT MARGARET THATCHER BECAME PRIME MINISTER ANOTHER YEAR UNDER A 14-YEAR DICTATORSHIP IN THE PHILIPPINES WHILST THE MARCOSES CONTINUE TO OUTLAST US.

What will we make of our years when we historicize them?

when we read them AFTER THE FACT?

when we try and be happier after going through their “tough times”?

Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick is a book of so-called “auto-fiction” – or “autobiographical fiction” – a book of “personal writing” – some even call it “psychological fiction”. It is a self-referential novel, as far as records show that the story of Sleepless Nights largely mirrors the author’s own personal life. Just like in the novel, in the 70s, Elizabeth Hardwick moved from her hometown so she could wear black smoke cigarettes go to jazz clubs have lots of sex join the Communist Party and go to the Writing Program at Columbia. The book is considered a classically important text, by and borne of the New York writing establishment, and the white guy who wrote the introduction to the latest edition of Sleepless Nights describes it beautifully as such:

“… an extraordinary apprehension of all that is elusive, haunting, unrecoverable in the human past and, simultaneously, of something proportioned, fixed and flexible in shape, an object to be contemplated: the book, or more precisely this book. What the book cannot hold is lost, and even what it can hold is lost, but the book is not lost. In some sense Sleepless Nights asks the impossible of writing, that it share in the life of which it is made, that it remain unfinished, that the door stay open. The result is an object at once open and closed, mysterious and fully articulated: a book written in the form of a life.”

(Geoffrey O’Brien, introduction to the 2001 edition of Sleepless Nights)

A book, in the form of my life, is this. I wasn’t thinking I was going to publish my writing in the matter of a book at all— until I saw what had accrued— pages upon pages— writing with the prompts almost daily— and it so happened that a vision for this book began to take shape.

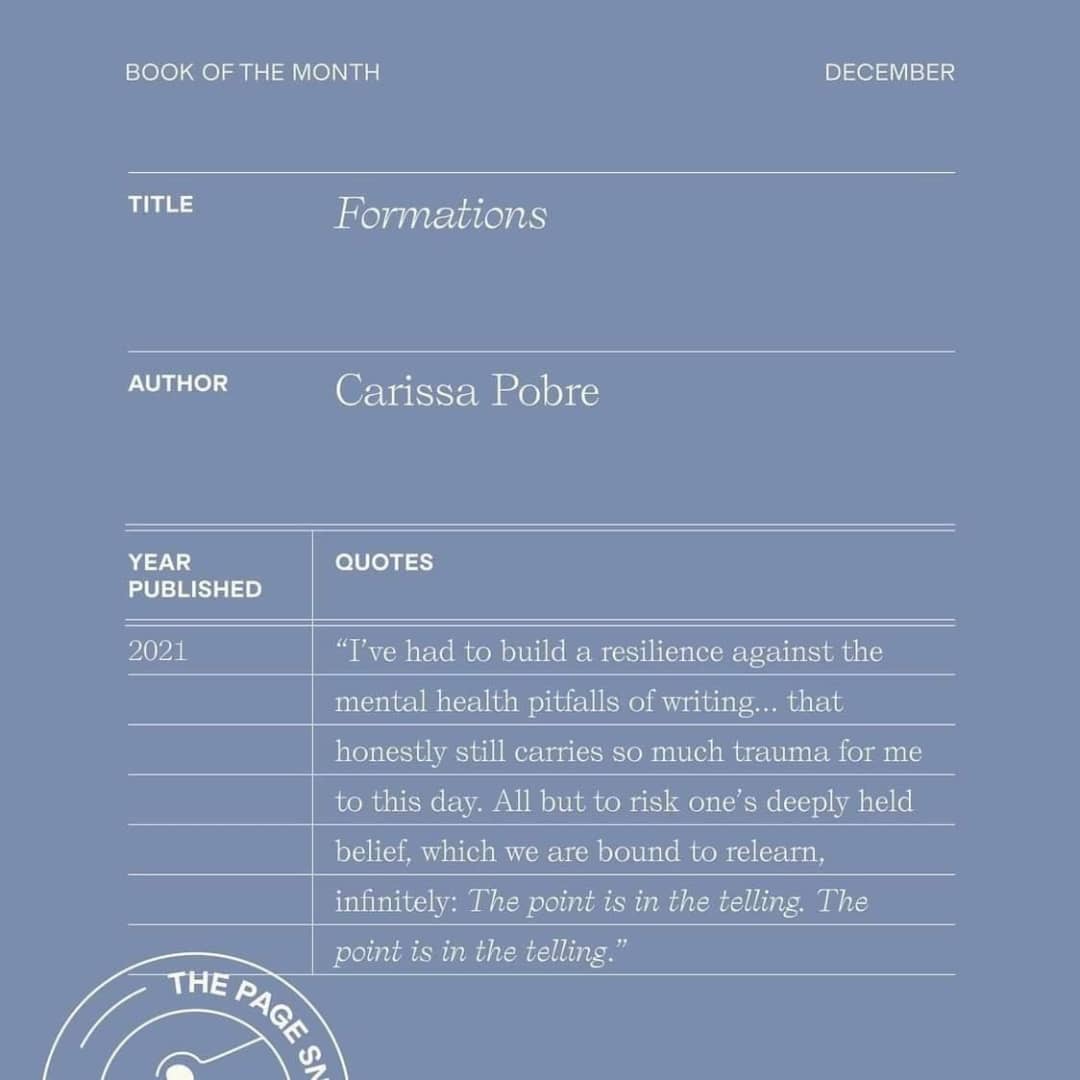

Last year, having a journaling practice helped me go back to writing in a way that was honest and not deceptive. I was writing regularly and consistently, my mouth was loose and open, and it was starkly different from the way my practice was as an Ateneo Creative Writing undergrad. Back then, when I was in your shoes (and I’m not the first to say something like this), every word was a Moment! of creation or Moment! of crisis, yung tipong DAPAT GUMUGUHO ANG MUNDO. The pandemic had forced me to rekindle my creativity needed to survive dire circumstances (even if on my part they were mostly psychological), and to reckon with my sense of self. It is through crisis that we ask the fundamental truths of ourselves, and in turn, what we realize is actually how enmeshed we are with one another.

Particularly when my book came out, I fell in love with the practices that readers have each cultivated with it. I know someone who has written over 60 pages from these prompts; someone who’s still at prompt 9 since last year but revisits them while waiting in airports; someone who deepened her tarot card reading practice from them; someone who started to draw in the space below the prompts in the book; someone who makes music and wants to respond to each prompt instead with sound; those who might just do the 30 prompts all over again; those who are just beginning to write now. “The point is in the telling,” Anne Carson says. Sometimes the point isn’t that art is the thing to be made, but to inspire artmaking in this long line of telling.

Of course, it’s nice to share this all in hindsight, after the fact, like an “author”. I suppose Formations is personal as personal writing gets, and writing like this emerges “from edges and shadows to arrive in the light”—borrowing from another beloved writer of mine, Rebecca Solnit. “Though that’s where [it] may be seen by others, that’s not where [that writing was] born.”

Many forms of mutual aid emerged especially during the early months of the pandemic, and at its worst peaks, and I like to think of the 30 Prompts similarly now: some kind of mutual aid for those who needed language, needed understanding and trust in the telling, needed a prompt to write like a respirator might help you to breathe.

It’s easy, too, to overstate the importance of writing and art. It’s, also, become cool to shit on those who overstate that importance. It’s because I have seen the effect of writing and art to address certain needs, even for smaller, privileged groups of people, that I guess I’m fine with being called as one of the believers. I saw the effect that the 30 Prompts and, yes, Formations have taken up in people’s lives, which ruptured me towards saying that art is, in fact, important; and I think it’s because we’ve institutionalized and/or marketized certain conditions around it that writers become “cringey”. Part of what my book has taught me is that writing outside of such conditions shows us how we are: We are readers and listeners of each other, relational, constantly unfolding, re-infolding and taking shape.

I find this idea of relationality in readership expressed so succinctly once again by Solnit. In her memoir The Faraway Nearby, she addresses the reader directly, inviting to reflect on our selves who personally engage in these processes of reading and writing:

“Who hears you? … We live inside each other’s thoughts and works. … You who read are now encased within a layer I built for you, or perhaps my stories are now inside you. … But exiting it is not an option; it is you.”

Somewhere further in the essays, she adds:

“The tragedy of the imprisoned, the unemployed, the disenfranchised, and the marginalized is to be silenced in this great ongoing conversation. … Listen carefully.”

Emergence and Craft

With Formations, I had given up preconceptions that things had to be written in a certain way. To be honest I attribute a lot of what I successfully rekindled with my writing practice to this change in perspective, brought to me by a global pandemic and writers like Jamison and Hardwick and Solnit and Lidia Yuknavitch and adrienne maree brown (among many others), who helped me eventually arrive here. I was writing like I was breathing, and because I was also writing freely outside of an institution, like a Writing Program, I had no reason to impress anyone. I just had to relate to someone.

Sounds trite, but it’s true. I copy-pasted my own journal entries into emails, into Telegram or Instagram posts—just to tell people I was okay, that I was not okay, and “the person I am right now, talking to you, is not the person I’m going to be later on… that I am someone who carries with me multiple selves… stacked of top of each other and all of them [having] their own emotional landscape to tend to at any moment… required to love multiple versions of [my]self throughout a day, throughout a week, throughout a month, throughout a life.” (quoting Hanif Abdurraqib, April 29, 2021)

These days, anytime I see anything written, I mostly wonder about the conditions that made that writing possible. Who or what is it asking us to interrogate? What interests me about the conditions that made this writing possible on the page? What can I learn or unlearn about those conditions?

Of course, for writers, craft is still important—not least, craft is important under conditions wherein writing is made to compare, compete, lay down the facts, communicate efficiently, or be studied. There are always going to be limitations in the system in which we choose to participate, or belatedly realize that we’ve been participating in all along. I will tell you now, my hypothesis is this: I don’t think the kind of writing born out of conditions like a pandemic, like a crisis, like “personal writing”, is going to care a lot about craft. It is going to care about needs, about mutual aid, about showing up for each other. If not for yourself.

Formations in book clubs and reading groups

Formations: The Shape of Process

Allow me to end this essaying with an offer.

When I launched and self-published my book in July 2021, I did with a book trailer that I did not expect would be a book trailer at all. It’s about a two-minute video, something of a micro essay or spoken word poem—call it what you like. I did realize eventually it would end up marketing the book, and I still don’t quite know how to market Formations as a self-published author, but that accompanying piece of writing did simply emerge for me, and I had fun playing with the video idea, working together with other creatives on it, before I put my book out there in the world.

I never felt like I planned for these things. All I did up until that point was to learn to listen to that thing presenting itself, that simply wants to take shape, to me and to the people in and around my life. Having gone through the small acts of construction work, of maintenance work, of relational work and play, I realized how every day which I wrote, shared in the life of which it was being written. Call that personal writing, if you will.

So my offer is this, heeding essayists like Solnit:

Writing is “not ultimately a journey of immersion but emergence.”

I don’t think you need to write everyday in a journal for that. Though, by all means. I have seen this and the 30 Prompts help. To put this in perspective, today some of the writers whom I continue learning from are people who have lives outside of it (and presumably don’t have time to write most days at all), and I don’t just mean writers who have day jobs. More than that, what I mean is they cultivate relationality—which some call community practice, relationship building, family in all forms of family there are on this earth, care in all its wonders and hardships on this earth. For us who have writing and language, readership is a relational practice and I constantly interrogate those relationalities. It is through such relations that something new does emerge—presenting itself, coming into view, and becoming known.

I’ll end here by sharing with you a definition of emergence (a scientific and ecological concept, which has also been framed by theories of change and social movements) that can simply inform the rest of our time together.

As explained by adrienne maree brown:

“Emergence is the way complex systems and patterns arise out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions … There are examples of emergence everywhere. Birds don’t make a plan to migrate, raising resources to fund their way, packing for scarce times, mapping out their pit stops. They feel a call in their bodies that they must go, and they follow it, responding to each other, each bringing their adaptations.”

Self-published as a small, independent print run in 2021, Formations by Carissa Pobre is available in local independent libraries (like the Alfredo F. Tadiar Library in San Fernando, La Union, as far as I know!). At this point, most of the copies of Formations are now in readers’ comforts and homes. You can get in touch with me if you would like to get a copy.